Using Thermocouples For More

Consistent Heat Treatment

by

Michael McGuire

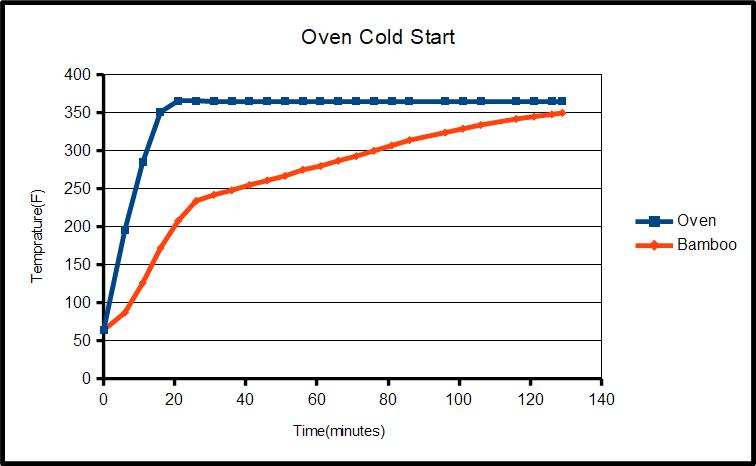

Below is the temperature vs time profile of my PID controlled oven and a bundle of bamboo strips in it monitored with a thermocouple attached to the bamboo.

In this test, the oven and the bamboo started at room temperature. The oven reached and stabilized at its set point temperature of 365 F in about 15 minutes. The temperature of the bamboo lagged the oven for quite a long time. If I had not been monitoring its temperature, I would have had no idea of what temperature cycle I had put it through. Surveying the literature on heat treating bamboo, I have found no mention of anyone monitoring actual bamboo temperature in their processes, let alone any mention of it lagging oven temperature.

An obvious question is why the lag. The likely answer is that it is due to the thermal properties of the water entrained in the bamboo. Between 0 C, the freezing point, and 100 C the boiling point, it takes only one calorie per gram of water to raise its temperature 1 degree C. At 100 C the next 1 degree rise requires 539 calories—the heat of vaporization. Until the water is boiled out the bamboo, the temperature rise is limited. In the plot above, there is an obvious change in slope of the bamboo curve at about 230 F. This is the point where steam started coming out of the oven. This is a bit above the 212 F / 100 C boiling point at normal sea level atmospheric pressure. This suggests that the higher temperature is required to generate the pressure inside the bamboo for the vapor to escape . As the temperature rises, proportionately more tightly entrained water can vaporized and get out.

This observed lag makes a strong case for monitoring. It is rather simple to do this with a thermocouple. A thermocouple is junction of a pair of wires of dissimilar metals. It produces a voltage which varies with the temperature of the junction. The most useful and common type of thermocouple is type K, chromel-alumel—color code yellow for positive, red for negative. Chromel and alumel are alloys which as a junction produce a relatively large change in voltage per change in temperature. Thermocouple wire is sold as a pair—the chromel and the alumel. It’s available both solid and stranded and in various gauges and with various types of insulation depending on the temperature range it has to stand. A number of vendors offer it. I got mine from McMaster-Carr. I recommend 24 gauge solid wire with fiberglass insulation. It runs around $1-2 per foot. This size is robust enough to not be delicate to handle, but should be easy to fish into an oven attached to bamboo without compromising the insulation of the oven. The junction can be made by removing the insulation and twisting the wires together. However at temperature the wires will oxidize and the junction becomes unreliable. It needs to be welded in some way. The ideal way is to form a little bead at the end which takes something as hot as oxy-acetylene. Spot welding also works. Failing that one can lay the twist on an anvil and hit it with a hammer to cold weld it. In use I whip the junction in contact with the bamboo with cotton string.

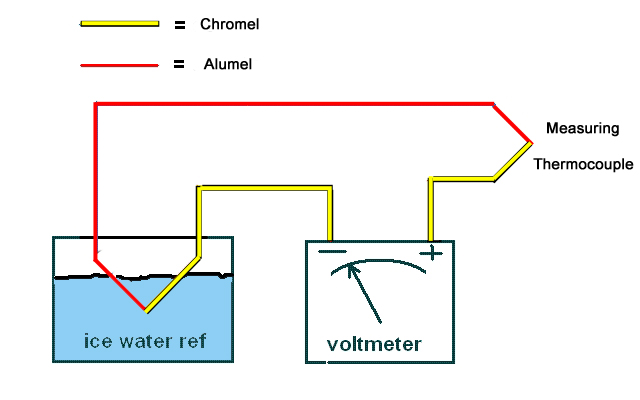

The most primitive measuring setup looks like this

Temperature is measured relative to the freezing point of water. Voltage is converted to temperature by consulting a table of temperature vs. voltage. In modern instruments the ice water reference is created electronically and the readout is digital in degrees. Some electronic multimeters have type K readout function. Harbor Freight offers one as cheap as $23 but it only reads out in degrees C. I favor a dedicated instrument, the DM6802A. Your favorite search engine will turn up a number of vendors with a price around $40. It will readout in either degrees C or F. It has two thermocouple inputs so difference measurements can be made.

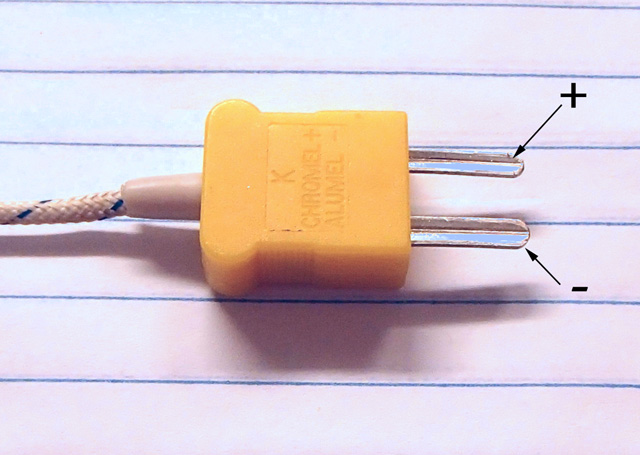

There is a special connector for type K thermocouples. It looks like this.

The metal parts are made of chromel and alumel. This is to avoid any possible error by introducing a junction with a different metal between the thermocouple and the readout which could cause an error. The voltages produced by thermocouples are in the millivolt range. There is a narrow pin for the positive (yellow) wire and and wide pin for the negative (red) wire. There is of course a matching socket on readout instruments. I got connectors from McMaster-Carr for about $4 each.

Given the way that the temperature of the bamboo lags that of the oven, what is a good time temperature process to use? There is a fair consensus in the literature, online discussion, etc., that half an hour at 350 F is good. But it appears that all or most of it has been done without monitoring the actual temperature of the bamboo. With monitoring, I found that half an hour actually at 350 F resulting in badly overcooked bamboo. The edges of beveled strips turn friable, crumbly. My guess is that it has been assumed that when a PID controlled oven gets to 350 F from a cold start, or recovers to 350 F in a hot oven start, the timing period should begin. As can be seen in the plot above, the bamboo is nowhere near 350 F half an hour after the oven has stabilized at its set point. If the process is stopped then, it is certainly not overcooked, but may not be very effectively heat treated. My current process is to run until the bamboo temperature just reached 350 F and then terminate the process. I have the oven set at 365 F to keep the rate of of increase ot the bamboo temperature from tapering off too much as it approaches 350 F. The bamboo treated this way seems quite sound as I plane it. There is a noticeable color change—darkening.

It seems likely that there will be variation in process times with different oven designs. Mine is a static oven—a 2 inch diameter aluminum tube with a heating cord wrapped around it. The tube temperature is stabilized with a PID controller. It’s insulated with fiberglass wrapped around it. An earlier smaller version is described in Power Fibers 55. My bamboo has had its nodes flattened, been rough beveled and bound into hexes with several hexes bundled together. To avoid the effect of a possible hot spot on the wall the bundle is wrapped with some thick cotton cord to offset it from the wall. The thermocouple is inserted through a hole in the end cap and whipped to the middle of the bamboo with cotton thread. Other types of ovens such as heat gun convection oven may well have somewhat different time-temperature profiles if the heat transfer to the bamboo is faster. If the bamboo is held in aluminum fixtures such as those Harry Boyd offers, heat transfer may also be improved. However working against improved heat transfer is still the need to vaporize the water entrained in the bamboo. I hope someone with one of these different kinds oven will take up challenge, and make and publish some measurements of bamboo temperature in their process.